Tipping the balance: Assessing patent infringement

In July this year, four years to the month after its introduction into UK law in the Supreme Court’s seminal judgment in Actavis v Eli Lilly, the court handed down its latest decision applying the ‘doctrine of equivalents’.

In July this year, four years to the month after its introduction into UK law in the Supreme Court’s seminal judgment in Actavis v Eli Lilly, the court handed down its latest decision applying the ‘doctrine of equivalents’.

This is the 18th time (by our count) that the UK court has applied the doctrine of equivalents in assessing infringement and the 11th time in which the patent has been found at least partially valid and infringed. In six of those 11 cases, infringement was not established under the ‘normal interpretation’. These statistics point to the likely impact of the doctrine in swinging the balance of power towards the patentee and away from the alleged infringer. In all seven ‘unsuccessful’ cases the patent was found invalid, although in four of these cases the judicial commentary confirms that if the patent had been valid, it would have been infringed under the doctrine of equivalents.

The A Ward decision is notable, not so much for the outcome (another patentee success), but because the patentee didn’t plead ‘normal’ infringement of the main patent in suit at all (although it did in relation to another patent) – the case on infringement was based solely on the doctrine of equivalents. This serves to further illustrate the potential impact of the doctrine on the rights of patent holders. In this article, we will recap on the nature of the doctrine, consider its impact on freedom to operate analyses, and discuss the emergence of a new defence to guard against infringement by equivalents.

What is the doctrine of equivalents?

The doctrine applies in circumstances where an alleged infringement doesn’t strictly fall within the claim of the patent in suit, and consequently there is said to be a ‘variant’.

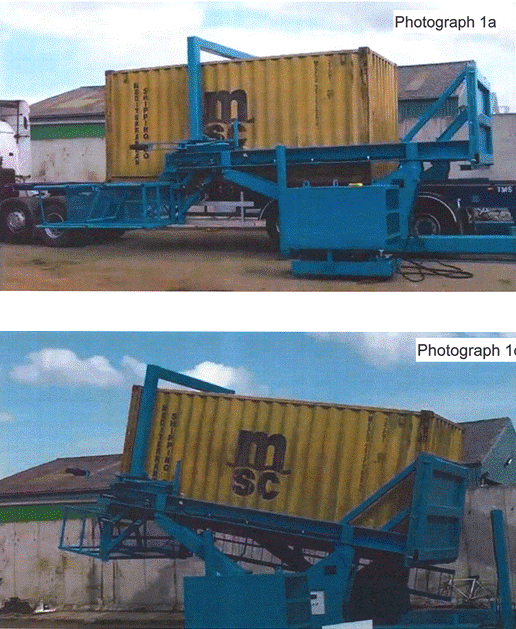

This scenario can be illustrated by the A Ward decision, concerning bulk material handling equipment, in which patentee alleged that two of its patents were infringed by Fabcon’s freight container tilting device. The photographs below show a freight container being reversed into the device in question, then the apparatus in the process of tilting the container.

Claim 1 of A-Ward’s parent patent begins with the words: “A freight container tilting apparatus (1) for tilting a freight container between a horizontal position and a tilted position for loading or unloading the container…”. It was common ground between the parties (certainly by the time of trial) that this characterising portion, along with most of the claim 1 integers that follow, were present in the Fabcon product, save for the following:

“a container lock…at the first and second ends of each of the first and second tilt arms, each container lock being configured to engage an end of the tilt arm with a side wall of the container” (our emphasis)

Whilst various arguments were run as to the nature and positioning of the ‘locks’, the key differentiator between the claim wording and Fabcon’s product was that the locks on the Fabcon device connected with the end (i.e. short) walls, rather than side (i.e. long) walls of the container, contrary to the wording of the claim. This is an example of a ‘variant’.

Under the doctrine as set out by Lord Neuberger in Actavis, the following three questions then become relevant:

- Notwithstanding that it is not within the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent?

- Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

- Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

In order to establish infringement, the patentee has to establish that the answer to the first two questions is "yes" and that the answer to the third question is "no".

What is the ‘inventive concept revealed by the patent’?

The answer to this question is key – it underpins each and every stage of the above test and is now critical to defining the monopoly enjoyed by all UK patents. Its importance is also borne out by the post-Actavis caselaw, with the majority of decisions grappling with this concept (through a diverse range of subject matter from ammo bags to treatments for sleep apnoea) and developing techniques for its identification.

The judges have attempted in various (and sometimes contradictory) ways to provide guidance on where the illusive ‘inventive concept’ can be found. For example, it:

- should be identified by reading the specification through the eyes of the skilled addressee;

- should be assessed by reference to the particular claim in question, rather than specification as a whole (despite Lord Neuberger’s words ‘revealed by the patent’);

- may relate to the characterising part of the claim (although in some of the cases it doesn’t!); and

- is not determined by the cited prior art.

The A Ward judgment offers further guidance, the judge holding that the fact a particular aspect of the invention (in this case, engagement with the side walls of the container) is mentioned countless times throughout the patent specification does not necessarily mean it is part of the inventive concept. The judge discerned the inventive concept from the way in which the patent articulated the problem to be solved, but also by its detailed teaching about alternative configurations and preferred features that those skilled in the art would appreciate are possible (in other words, if a feature has a number of alternative embodiments, this suggests that a particular embodiment will not be part of the inventive concept).

Importantly for the outcome of this particular case, the judge found that the precise means of locking the container fell outside the inventive concept of the patent. The judge also rejected Fabcon’s submissions that the patent did not disclose an inventive concept at all.

So what exactly is it, in the context of the doctrine of equivalents? The inventive concept has been described in various ways, perhaps most clearly by HHJ Hacon in Regen v Estar in the following terms: “I take the inventive concept or core of the invention to be the new technical insight conveyed by the invention – the clever bit – as would be perceived by the skilled person.”

This was elaborated on in the A Ward decision, which also illustrated the importance of expert evidence in helping the court to determine the inventive concept, the judge noting: “it can be informative for the Court to look closely at what it is about an invention that gives an expert in this field a ‘buzz’, and Mr Dekkers [A Ward’s expert] was clearly energised by what he considered to be the “brilliance”, or the clever bit, that he perceived in the invention”.

Even when you have identified it, the inventive concept can be difficult to articulate, as the judge in A Ward found – needing no fewer than 126 words to do so. In short, the judge found it was to do with the capability of the apparatus to receive and tilt the containers, but importantly did not include ‘the specific details of how and where the apparatus engages with the container’.

Substantially same result/substantially same way:

Once both the inventive concept of the patent has been identified, the court can apply the first limb of the test – does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the inventive concept. Naturally, a key determining factor is whether the relevant feature(s) of the claim (which are not present in the alleged infringement) fall within the inventive concept. If they do not, it is likely the variant will achieve the same result in the same way as the inventive concept, and the answer to the first limb will be ‘yes’ (as has been seen in a number of the cases including Technetix and A Ward). Conversely, if the relevant feature is considered a part of the inventive concept (the ‘clever bit’) then naturally the variant is more likely to have an impact (a different result, or in a different way).

This emphasises the importance of how widely, or narrowly, the inventive concept is defined and gives rise to a possible tension when arguing a case in which the patent in suit is also alleged to be invalid for lack of ‘inventive step’ (notably a different, but overlapping concept to ‘inventive concept’). Surviving the validity attack may require argument that many aspects of the claim are inventive, but that could equally lead to a finding that the variant is within the inventive concept and thus not ‘equivalent’. A tightrope can emerge, making the clarity of the expert evidence all the more important.

In A Ward, having found that the variant – the precise means by which the apparatus engaged with the container - was not part of the inventive concept, the judge considered limb 1 of the test. It was common ground that the variant achieved substantially the same result (securing the container to allow tilting) but Fabcon argued that it did so in a substantially different way, due to the means of engagement with the ends rather than sides of the container. However the judge rejected this, having found that the precise means of engagement was not part of the inventive concept. Other arguments including the differences in forces exerted on the container were also rejected, the judge finding the result was achieved in substantially the same way and so the answer to the first Actavis limb was ‘yes’.

Limbs 2 and 3:

Limb 2 of the Actavis test was articulated clearly by Birss J in the High Court decision of Evalve :“The skilled person is treated as knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention. The question is whether it is then obvious to them that the variant achieves that result in substantially the same way as the invention.”

It is notable that in all cases where the doctrine of equivalents has been applied in the context of infringement (with the patentee having successfully overcome limb 1 of the Actavis test) limb 2 and 3 have subsequently been satisfied (often with little judicial consideration). Arnold LJ in the High Court decision of Akebia noted “there will rarely be scope for a negative answer if the answer to question (i) is “yes”, and I do not consider that there is in the present case”.

Limb 3 of the Actavis test focuses on whether a reader of the patent would have reached the conclusion that the patentee intended strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claims of the patent as an essential requirement of the invention. Arnold LJ in Akebia noted that in this context, what mattered is the reason why the addressee would think that the claim was limited in the relevant respect and in that case “it is clear that the skilled team would conclude that the patentee intended that strict compliance with the normal meaning of “Compound C” was an essential requirement of the invention of claim 17A” (albeit the first limb of the Actavis test had also not been satisfied, so this finding had no consequence on the outcome of the case).

As such, where the patentee has been able to satisfy the first limb of the Actavis test, the following two limbs have to date always been met. Similar to the preceding cases, in A Ward, limbs 2 and 3 of the Actavis test were not a point of dispute between the parties, so these limbs were satisfied with little judicial discussion.

The introduction of infringement by equivalents has undoubtedly shifted the goalposts in favour of the patentee. The scope of protection afforded by a patent is apparently broader than it once was. And so, what can be done by those who might come under fire?

FTOs

Firstly, at an early stage, action can be taken by re-formulating the approach to freedom to operate (FTO) analyses. Conscious of the potential breadth of a patent’s monopoly, it is important to have a critical eye on any perceived differences between your planned technology and not only the claims of the patent, but also its inventive concept. This is not an easy task, as often the inventive concept of the patent is not clearly articulated in the patent itself, and so early engagement of experts in the technology is paramount. But by focussing on the questions of (1) what particular result the patent achieves, and (2) how it achieves that result at least starts the analysis in the right direction.

Of course, the canny patentee will also be looking to circumscribe the inventive concept in such a way as to capture potential or anticipated workshop variations, knowing that the doctrine of equivalents gives extra protection around the edges. This leads to an understandable call for further rebalancing in favour of the potential infringers, or at least certainty.

A fourth limb? The Formstein defence

The courts have made it clear that the doctrine of equivalents applies to the infringement of a patent, but not as to its validity. There, the traditional tests on novelty and inventive step (obviousness) apply. However, there is potentially emerging an additional defence which might assist alleged infringers.

Under German and Dutch laws, which have recognised the doctrine of equivalents, a further question (or Actavis limb 4) has been formally adopted. This limb 4 effectively looks at the variant which has been identified and asks “at the priority date of the patent, taking into the state of the art, is it new or obvious to a person skilled in the art?” If the equivalent product/process was known or obvious at the priority date, it does not infringe.

There have been a couple of attempts to persuade the English courts to adopt a similar approach. Notably, it was raised in the High Court in Emson. But there, the patent was found to be invalid for lack of inventive step, and so the judge was not required to consider Formstein, as the question of infringement was not determinative of the outcome. Had the patent been valid, the judge found that it would have been infringed on equivalents. The finding of invalidity was unsuccessfully appealed. A similar question with a similar answer was run before HHJ Hacon in Technetix.

The High Court in Facebook v Voxer IP has come closer to approving Formstein. In that case the relevant patent was found to be invalid and not infringed. Infringement by equivalents was argued unsuccessfully, but Birss LJ did say, obiter, that had he needed to, he would have held that the equivalent device lacked novelty/inventive step. He considered that a Formstein defence promoted certainty and was consistent with the approach taken in other European Patent Convention countries.

As recognised by HHJ Hacon in Technetix, this is probably a decision for the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court, but given the judicial nod from Birss LJ (albeit in the High Court) it seems reasonably safe to recommend that alleged infringers should look to run this defence, if available to them.

And so although in the UK patentees, most recently in A Ward, are reaping the rewards of the doctrine of equivalence, a further rebalance may shortly be coming down the track.

First published in the Intellectual Property Magazine - A Ward Attachments Ltd v Fabcon Engineering Ltd, in October 2021, and co-authored by Mark Daniels, Nick Smee and Jess Johnson.

Contact

Mark Daniels

Partner

mark.daniels@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)121 237 3993