Originally published in Healthcare World by Gerard Hanratty, Browne Jacobson.

The 10-Year Health Plan for the NHS in Britain is underpinned by three bold moves to improve public health while driving efficiencies. Gerard Hanratty and Charlotte Harpin, partners at UK and Ireland law firm Browne Jacobson, explain why this is as much a legal project as it is a clinical or operational one.

The NHS stands at a crossroads. With mounting pressures from demographic change, rising demand and persistent challenges in access and outcomes, the 10-Year Health Plan sets out a bold vision to transform the service for future generations.

At its heart, the plan is structured around three transformative themes: shifting care from hospital to community, moving from analogue to digital, and pivoting from sickness to prevention. These are themes we see emerging around the world.

Each of these themes is underpinned by a complex web of legal considerations, which will shape the success of the reforms and the experience of patients and professionals alike.

Alongside this, the plan actively seeks to expand private provider involvement and looks to attract international investors – particularly in life sciences, digital health and clinical trials.

From hospital to community: Redefining where and how care is delivered

The first pillar of the plan is a decisive move away from hospital-centric care towards neighbourhood-based, community-focused services. This shift is not merely operational – it requires a fundamental redefinition of statutory responsibilities and the legal architecture of the NHS.

A key innovation is the creation of neighbourhood health centres (NHCs), which will serve as ‘one-stop shops’ for patient care – integrating NHS, local authority and voluntary sector services.

Legally, this demands new legislation to formalise NHCs as primary points of care, with clear statutory definitions and governance structures. The introduction of new contracts for GPs – enabling them to work across larger geographies and lead neighbourhood providers – raises significant legal questions that will be answered around procurement, competition law, and the allocation of roles and liabilities among providers. Equally, integration with local authorities and the third sector will require robust legal agreements to govern co-location, data sharing, safeguarding and joint commissioning.

It is anticipated new legislation will amend the current statutes and the new approach must comply with the NHS Act 2006, the Care Act 2014 and data protection laws, ensuring patient safety and confidentiality are not compromised as care moves closer to home.

Clearly, patient rights are central to this new model. The emphasis on personalisation – through care plans, personal health budgets and digital self-management – brings into play legal frameworks around informed consent, capacity, and the right to refuse or direct care.

This will mean, subject to any amendment, the NHS Constitution, Mental Capacity Act 2005 and equality legislation must all be carefully navigated to uphold patient autonomy and prevent discrimination, particularly as services are reconfigured.

For a safe and robust implementation, then, regulatory oversight will also need to adapt. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) and other regulators must develop new inspection and quality assurance frameworks for integrated, community-based care. It will be interesting to see how foundation trusts, integrated health organisations and other providers are regulated against licence expectations in the future.

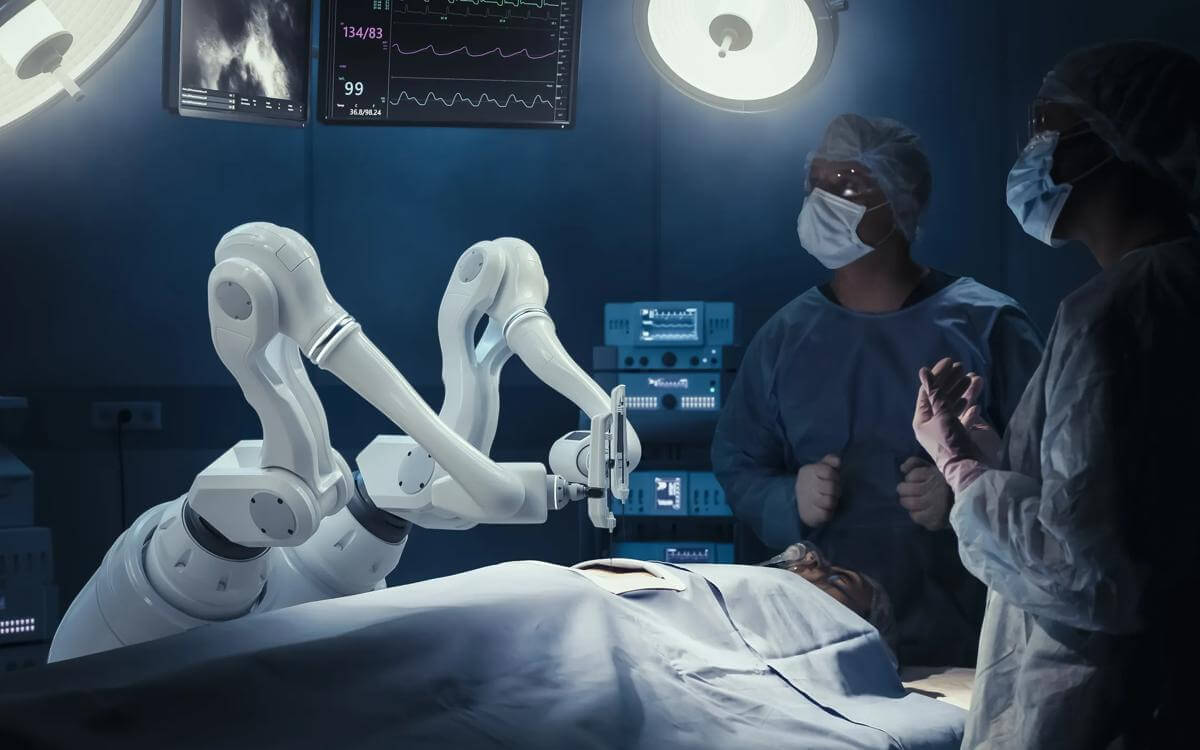

From analogue to digital: Harnessing technology for a modern NHS

The second theme of the 10-Year Health Plan is the digital transformation of the NHS. Central to this is the introduction of the single patient record (SPR), which will consolidate all medical records into one secure, authoritative account accessible by both clinicians and patients. This is not just a technical challenge – it is a legal revolution in data rights and access.

New legislation will require every health and care provider to make the information they record about a patient available to that patient, with the ambition for default access via the NHS App by 2028.

The Data (Use and Access) Act 2025 underpins this change – enabling, when necessary, patients’ rights to fast, transparent and secure access to their own health data. Compliance with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 remains paramount to ensuring patient confidentiality, security and informed consent.

The expansion of the NHS App and the SPR means more patient data will be shared across settings, raising the stakes for data protection and privacy. The plan promises a rigorous approach to data security, with a redesigned opt-out system informed by public engagement. It will also ensure patients have greater control over how their data is used, and legal reforms will facilitate the use of anonymised (or synthesised) NHS data for research and service improvement, provided it does not contain identifying information.

The establishment of the Health Data Research Service (HDRS), in partnership with the Wellcome Trust, aims to streamline access to health data for researchers, accelerating medical breakthroughs and improving patient care. However, there is still some complexity to be navigated so that agreements ensure the NHS and patients retain ownership of data, and that any commercial use delivers value back to the NHS. This raises questions of intellectual property ownership, benefit sharing and contractual arrangements with private partners.

For the move to digital to work, then it is clear that digital inclusion is another critical legal issue. The NHS App and digital services must be accessible to all, including those with disabilities or low digital literacy, in compliance with the Equality Act 2010 and accessibility standards.

Further, as digital tools and AI become integral to care, legal responsibility for clinical decisions, data accuracy, and system failures must be clearly defined. Providers must ensure that digital systems are safe, reliable and compliant with medical device and AI regulations, with clear frameworks for consent, liability and redress in cases of data breaches or harm.

From sickness to prevention: A new legal mandate for public health

The third theme of the plan is a shift from treating sickness to preventing ill health. This redefines the statutory duties of the NHS, positioning it as an active agent in prevention and public health.

A key example of legislation underpinning this idea is in the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, which will make it illegal to sell tobacco to anyone turning 16 in 2025 or younger when implemented. The idea is to effectively create a smoke-free generation.

However, this requires robust enforcement mechanisms and compliance with consumer protection and public health laws. Mandatory healthy food sales reporting for large food companies would also introduce new legal requirements for transparency and compliance, which opens potential challenges around data privacy, commercial confidentiality and competition law. It clearly shows the need to balance public health measures with individual rights, whilst seeking to incentivise healthy behaviour.

An internationally-based aim is the government’s ambition to implement universal newborn genomic testing and population-based polygenic risk scoring, although it does raise questions around consent, data protection and potential discrimination. While the expansion of genomic and health data collection must comply with the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018, it does raise real opportunity for the international health community to collaborate and find solutions to some of the most debilitating health problems which we face today.

It will require robust ethical oversight, with legal frameworks ensuring individuals retain the right not to know their genetic risk, and that data is not used in a discriminatory manner, in line with the NHS Act, Equality Act 2010 and human rights legislation. However, it does raise hope for millions of people that we will develop a much greater understanding of the human body and the conditions that can afflict it.

Final thoughts: A legal framework for transformation

The 10-Year Health Plan for the NHS is as much a legal project as it is a clinical or operational one.

The three big moves underpinning this vision – from hospital to community, analogue to digital, and sickness to prevention – will only succeed if supported by robust, adaptive legal frameworks.

These must protect patient rights, ensure data security, promote equality and provide clear lines of accountability for all stakeholders.

As the NHS embarks on this ambitious journey, the law will be both a safeguard and an enabler, ensuring the founding principles of universal, free, and high-quality care are not only preserved but strengthened for the future.

Contact

Kara Shadbolt

Senior PR & Communication Manager

kara.shadbolt@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)330 045 1111