Health care apps – Part 1 of 2: Exploring the ins and outs of intellectual property (IP)

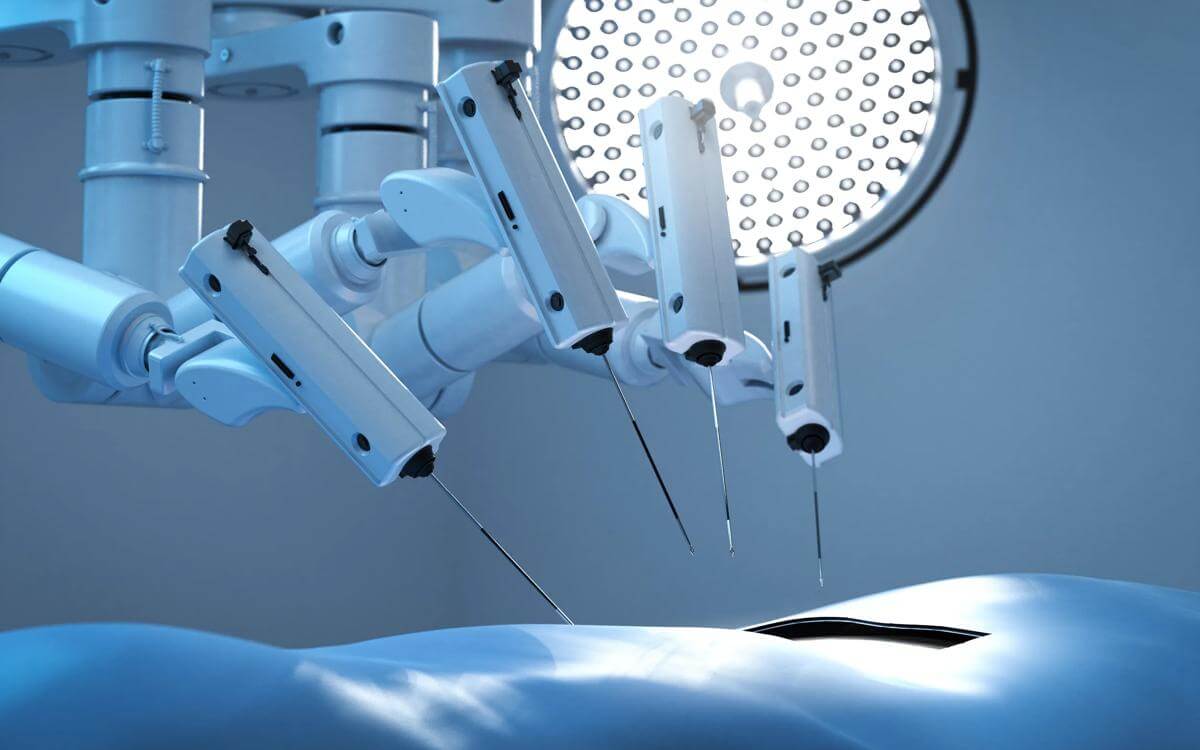

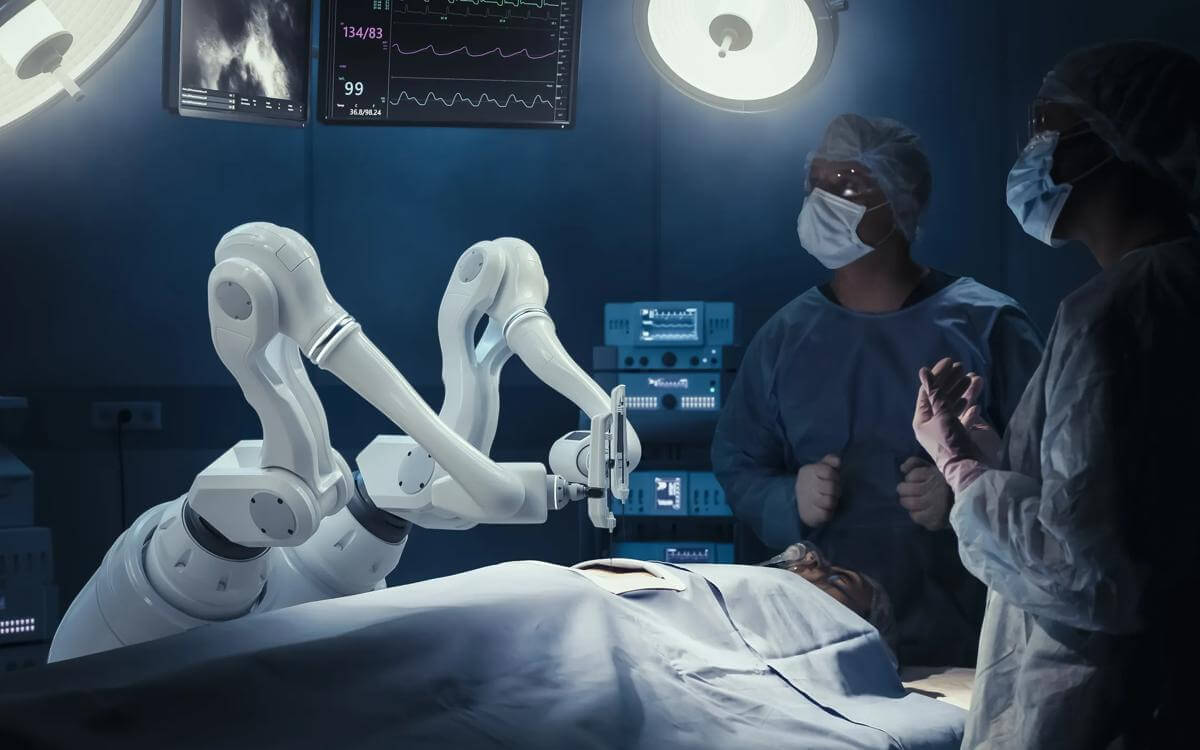

The adoption of smart technology solutions by the health and care sector has exploded in 2020. The pandemic has driven the sector to increase its use of smart phone technology solutions (Apps), an example of which is conducting video consultations and assessments. Adoption has historically been slow to develop across the sector generally, potentially due to perceived risks in maintaining integrity of special category personal data.

Now, more health and care providers are transitioning to greater use of Apps; the Covid-19 pandemic has propelled providers to implement systems which can assess an individual’s needs remotely.

In the ‘new normal’, the sector will increasingly adopt and implement its use of Apps to assess and deliver person-centric health and well-being advice and services. The Apps which are created will be in demand, competition is likely to be high and the potential commercial value to providers is significant.

Apps are created by combining software with data (in its broadest sense and by use of personal data). Part 1 of this two-part series will explore intellectual property rights in the App and how these are protected commercially, whilst Part 2 delves into data confidentiality.

Intellectual property rights

Apps are largely software which consists of lines of code or instructions which a computer reads and executes. There are two types of code. Source code is the language which humans read and write. This source code is then compiled to create object code which is only capable of being read and executed by a computer. This code is often protected by copyright. Health related Apps may (depending on the service need) require validation which relies on the use of data, in anonymous and identifiable forms. This data is often collated and contained in a database, which is also protected by copyright as well as being protected as a database under the Database Regulations (also known as a ‘Sui Generis’ right).

A market ready App may also have protection in the form of registered and unregistered trade mark rights but these are not considered further here.

Copyright protects the expression of ideas and not the idea itself. It is possible for two identically functioning pieces of software to exist without one being copied from the other. In this case, neither author would be liable for copyright infringement of the other’s work.

Copyright in Apps will subsist in each of:

- the source code (e.g. C programming language and the code written by the software developer);

- object code (being the numerically coded instructions only capable of being read and executed by a computer, e.g. 0 and 1’s);

- the visual display elements including typographical layout of the App (which the end-user sees); and

- all documentation which records the development (e.g. technical file for the purposes of regulatory submission) as well as any instructions for use or manual.

The App provider or commissioning party will want to ensure it owns and has exclusive rights to use this copyright as well as ensuring it has physical access to the records. Physical access is addressed by putting in place terms which oblige any 3rd party developer to deliver up all such materials to the commissioner. If refused, the commissioner has a right to claim against the developer for breach of contract which can be remedied by specific performance and/or damages being awarded.

Data in its simple form is not protected by law. Personal data cannot be legally owned; it is always subject to the rights of the individual to which the data relates. However, if personal data is anonymised and compiled to create a database of information, that database may be protected by law as an intellectual property right. To the extent any data is shared with 3rd parties, suitable confidentiality obligations should be put in place with any recipient of such data to ensure there is a direct written and enforceable obligation on the recipient to only use any data in accordance with the purpose for which it is provided. Any subsequent database creation which may occur is then subject to the terms discussed below.

Ownership

It is a common mistaken belief that a commissioning party owns the copyright in any deliverable.

In law, the first owner of copyright is the author, unless (i) the copyright is created by an employee in the course of their duties; or (ii) the parties agree otherwise in writing.

Employers of software developers will own the copyright in the work authored by its employees. This is the position under English law even if the employee’s contract of employment is silent. However, it is good practice to ensure that all employment contracts expressly set this out to minimise the risk that an employee may dispute the position.

Third parties (e.g. sub-contractors) will own the copyright in the work they create unless there is written agreement to the contrary. Where you are the commissioner of any work, you will need to ensure that the terms of any agreement:

- Vests full legal title to the copyright (and other IP rights) in you by way of assignment;

- Includes a prospective assignment of copyright to ensure legal title to any copyright which does not exist at the date of signing the agreement (e.g. the work to be provided under the services) vests in you once created;

- Imposes a direct contractual obligation on the third party to deliver up to you the source code, object code and any other documentation recording the software creation and development so that you have physical possession of it;

- Includes a promise from the third party that the work provided to you has not been copied and does not infringe the intellectual property rights of any third party;

- Includes a statement that the work provided to you does not use open source software (OSS) and if it does that all uses of OSS are subject to your consent prior to it being used in the commissioned work; and

- Includes a further assurance clause which requires the third party to do any future acts which may be required to ensure legal title to the copyright vests fully in you.

Including each of the above points goes a significant way in addressing potential risks that you are subject to a future claim being made against you for intellectual property infringement.

Open source

App developers may use open source software or code libraries (OSS). OSS is copyright accessible from the web which is made available for use by third parties by the owners of it. It is often used by third parties on the misunderstanding that they can use it however they choose, without restriction. This is not true.

OSS is often subject to licensing terms (e.g. the GNU General Public License (often abbreviated to GPL)). Use of the GPL is subject to users complying with certain conditions, including: displaying a copyright notice; disclaiming any warranty; keeping GPL notices intact and providing a copy of the GPL. It is important to note that any modification and redistribution of the software requires the same conditions to be applied to its future purpose. This is a potential risk if the App is to be marketed commercially as a third party could access the same software and duplicate the App without the risk of copyright infringement. This is also why the visual elements and any technical file are important as they provide additional copyright protection in the event that the App’s code was created from OSS software as if these are copied, the copying is potentially copyright infringement.

Some of the risks with using OSS in technology solutions include:

- If the App is subject to public licensing terms, there is a risk that you may be compelled to publish the source code for others to use. This reduces its commercial value as it can be copied and modified by a 3rd party (who may be a competitor) with relative ease. This risk may be balanced against the cash investment in the project. Any proposed use in breach of the licensing terms may result in a claim being made for intellectual property infringement.

- If you use OSS you will also need to be careful about the terms under which you make the App available to end-users. For example, restrictions on use which are inconsistent with the GPL, or making any warranty statements that you own the App and any OSS subsisting in it, may conflict with the terms under which you are permitted to use the code. This conflict may give your App users a contractual right to claim against you for breach of contract which may result in a damages award or contract termination.

- OSS is potentially at increased risk of manipulation by 3rd parties seeking to expose software vulnerabilities. The App is then at increased risk of being subject to a cybersecurity incident. In health and social care, it is more likely that personal data is a component of any App which may increase its risk should the intention of any cyber-attack be to obtain personal data for fraudulent purposes. Therefore, continued support and maintenance of the App is crucial. Loss of personal data is a significant business risk. The consequences may include an investigation by the ICO, fines and/or penalties as well as potential claims being made by data subjects whose personal data was illegally accessed. Additionally, any associated publicity may adversely affect the reputation of the business and which may reduce consumer confidence.

Conclusion

Apps have a valuable place in the healthcare market and will likely continue to attract significant investment to produce better ways of delivering healthcare solutions. However, failing to address the above risks prior to starting App development has the potential to thwart any project timelines for implementation and commercialisation, but is also at increased risk of being subject to a future dispute.

If you would like to know more, please get in touch.

Contact

Mark Hickson

Head of Business Development

onlineteaminbox@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)370 270 6000