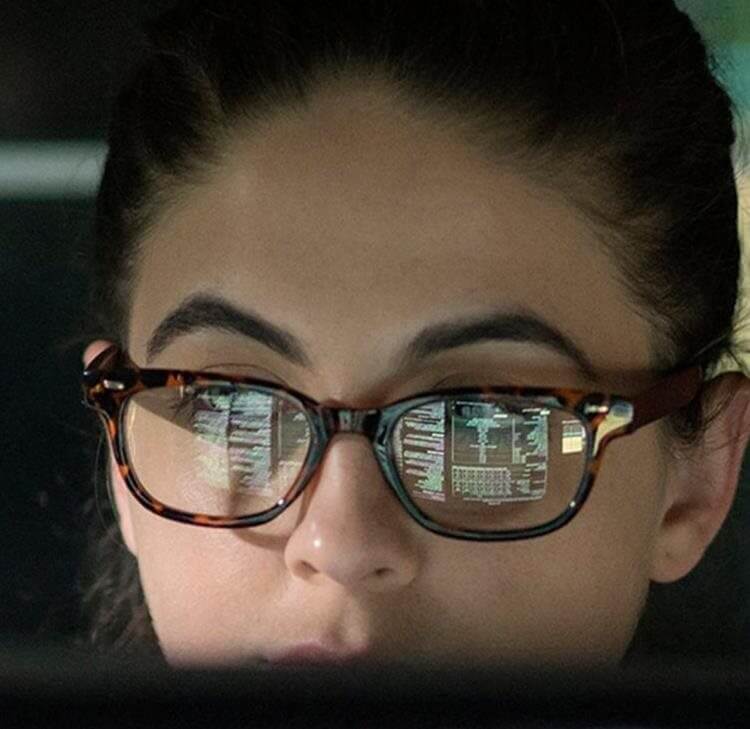

As AI becomes part of day to day life, the risks of its use within the justice system are becoming more apparent, resulting in the UK judiciary being issued refreshed guidance on the topic. However, the recent decision of the Appointed Person (AP) in a trade mark opposition appeal (concerning rival PROHEALTH marks), may be the first time this issue and its potential consequences has been highlighted in an IP dispute in the UK.

Within his decision dismissing the appeal, the AP called for “a very clear warning” to be included in any correspondence sent from the Registrar requesting submissions, skeletons or other documents from the parties. This should set out explicitly the risks of using AI for legal research and the drafting of such documents as well as the potential consequences of putting fabricated citations before the Registrar or Appointed Person.

The AP here stressed this warning should be sent to litigants in person (such as the appellant) but also all professional representatives. He observed that in previous UK court judgments, legal professionals had already been censured for incautious reliance on AI (e.g. Ayinde v Haringey [2025] EWHC 1383 (Admin))

In these trade mark opposition proceedings, the appellant had been open about using Chat GPT to draft his grounds of appeal and skeleton argument. Included in his grounds was a list of cases each with a citation and a “quote”. The AP noted that although the cases were real, three of the purported quotes were not found in the decisions cited. In addition, the appellant’s skeleton argument included six cases with summaries but the refences for two of these were wrong and the summaries of three of them substantially misrepresented their content.

The AP was sympathetic to the allure of using AI to litigants in person in the appellant’s circumstances. He appreciated that limited access to legal aid and other funding arrangements meant many could not afford representation and would know little about trade mark law themselves.

They may therefore think that anything AI created would be better than what they could produce themselves. However, “an unrepresented person is still under a duty not to mislead the court” and “it does not matter whether fabrication was arrived at with or without the aid of generative artificial intelligence”.

Unlike the UK courts, neither the Registrar nor the Appointed Person has the power to deal with contempt summarily. It is also unlikely law officers can bring contempt proceedings in the courts in relation to any improper actions before the Registrar (as it is an administrative tribunal). Wasted costs orders against a party’s representative are also available in the courts but cannot be made in Registry proceedings.

However Appointed Persons and Hearing Officers can make costs orders above the standard modest scale of Registry proceedings, where a party has acted unreasonably. The AP’s view was if a party puts fabricated material before the tribunal the starting point should be that “off-scale” costs will be awarded. In this case that did not happen, but only because the contents of the respondent’s skeleton argument (which was drafted by its trade mark attorney) was also strongly criticised.

Conclusion

The AP’s decision considers the position when the use of AI leads to misleading submissions being made in disputes generally. It summarises the sanctions that can be imposed in this situation not only against litigants in person, but also against professional representatives (which include a referral to their regulating body – such as the Bar Council, SRA or IPReg).

It also considers all the sanctions that can be imposed by the Registry but also by the courts. It is therefore worthwhile reading for anyone seeking the considerable assistance AI can provide when dealing with legal disputes. Tools such as ChatGPT:

“can produce apparently coherent and plausible responses to prompts, but those coherent and plausible responses may turn out to be entirely incorrect. The responses may make confident assertions that are simply untrue. They may cite sources that do not exist. They may purport to quote passages from a genuine source that do not appear in that source” (Ayinde v Haringey).

This means there is a duty to always very carefully “check the accuracy of such research by reference to authoritative sources”.

Contact

Mark Hickson

Head of Business Development

onlineteaminbox@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)370 270 6000

Related expertise

You might be interested in

Press Release

Supreme Court decision on Oatly using 'milk': Legal comment

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: January 2026

Legal Update

Kohler Mira v Norcros: Key lessons in purposive construction for patent drafters

Legal Update

Protecting your brand from 'genericide': Lessons from Dryrobe v D-Robe

Legal Update

Court of Appeal says ‘no’ to co-branding but dismisses copyright claim in AGA conversion case

Legal Update

Rise and shine: The European breakfast directive’s new year transformation

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: November 2025

Legal Update

Getty Images’ copyright not infringed by Stability AI making its Stable Diffusion model available to users in the UK

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: September 2025

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: July 2025

Legal Update

Trade mark dispute risks: AI in legal document drafting

Press Release

Browne Jacobson a ‘discerning choice’ for clients with ‘IP-rich deals and complex litigation’ - as team ranks for both IAM Patent 1000 and IP Stars 2025

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: May 2025

Legal Update

Trade mark strategy in a global market

Legal Update

Advertising trends: Influencers, intellectual property and image rights

Legal Update

Metro’s Runs Afowl of Morley’s Marks in the Court of Appeal

Legal Update - IP insights

IP insights: April 2025

Opinion

What’s in a shape? The impact of 3D registered trade marks on glucose monitoring kits

Legal Update

One to watch: Oatly appeals to the UK Supreme Court in continued fight for its trade mark

Press Release

Intellectual property (IP) predictions for 2025

Legal Update

Alcohol charity on the “Naughty List” for attempts to trade mark “DRY JANUARY”

Legal Update

EasyGroup proceedings defeated by jurisdictional challenge

Legal Update

Veganism and manufacturing: IP protection

Press Release

Browne Jacobson’s intellectual property lawyers ranked experts in World Trademark Review guide 2023

Press Release

Court of Appeal makes plea for legally enforceable arbitration for FRAND disputes

In the ongoing complex litigation between Optis Cellular Technology LLC and Apple Inc., the Court of Appeal ([2022] EWCA Civ 1411) has upheld the High Court’s findings that implementers of standard-essential patents (SEPs) cannot refuse to accept a FRAND license and continue activities in the meantime which constitute infringement: that party must commit to accept a court-determined license if it wishes to avoid an injunction.

Published Article

AI generated designs on retail products

Every AI will have its own terms of use. DALL·E 2’s Terms of Use dated 3 November 2022 specify that as between a user and Open AI, a user owns their prompts and uploads. Open AI also assigns to the user all rights in any images generated by DALL·E 2 for that user (subject to the user complying with those Terms of Use, and to a licence to use inputs and output to develop and improve the services).

Press Release

Browne Jacobson’s IP experts shine silver in world’s leading trade mark lawyer rankings

Opinion

Sky’s overly broad trade marks narrowed as found partially invalid for bad faith

Lord Justice Arnold has applied the guidance of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to the evidence before him, in the long standing trade mark dispute between Sky and Skykick.

Legal Update

Amazon not liable for merely storing third party’s infringing goods

At a time when Amazon is fielding large spikes in demand amidst the coronavirus pandemic, the online retail platform will welcome the ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) received on 2 April 2020.

Legal Update

Domain names as IP rights

On-Demand

How to commercialise your IP: licensing, spin outs and JVs

Our expert panel, comprised of IP and corporate law specialists, will be discussing IP commercialisation strategies, their benefits and pitfalls, drawing on experience across the private, public and higher education sectors.

Published Article

O/281/19 Revocation (Device Marks) – 23 May 2019

This decision is a good example of how the IPO approaches non-use challenges, and an insight into the economics of gift shops at public parks.

On-Demand

Parallel Imports - what brand and IP owners need to know

Parallel importers seek to exploit price differentials for goods sold in different countries. The EU principle of exhaustion of rights prevents businesses from enforcing their IP rights to restrict this secondary trade within the EU if the goods were first marketed in the EU with their consent, other than in limited circumstances.

Legal Update

“Utterly horrified” masters and “blatantly inadmissible” evidence

The sole result for a search on Westlaw for the phrase “utterly horrified” is an interesting decision from Mr Justice Arnold on June 12 2019 about evidence in passing off proceedings.

Press Release

Browne Jacobson scores victory for Wolverhampton Wanderers over badge copyright claim

Browne Jacobson is delighted to have assisted Wolverhampton Wanders Football Club to successfully defend a copyright infringement claim made against it which relates to the club’s iconic wolf head design. The club has used this design as an element of its badge since 1979.